Ibhaliwe

And research begins…

Acquaintance.

The first step was the acquaintance with the language and culture. Building upon memories from a recreational visit to South African Xhosa families, I started listening to spoken speech in Xhosa with subtitles, listening to songs, reviewing imagery. With the help of one of the interviewees an audio library of all consonants in Xhosa language was created, which helped to focus on each phoneme separately, distinctly, and learn how it is physically generated in the mouth. (Sample mp3 files with a GC, NX and Q cliques below.)

Interviews.

Video and written interviews were conducted with a set of questions ranging from asking for objectively accepted details (like Xhosa cultural traditions, history, literature, music, art, science and design) to subjective opinions regarding psychological representation of Xhosa nation as a whole, critical analysis of its role in South African, continental and global history, intuitive suggestions regarding written script as well as personal predictions and wishes regarding the practicality of it.

Concept drafts.

All the documented details were used to feed design solutions presented below, following widespread practices of written script modeling. I have been taking inspiration from written script creation logic used in many cultures, such as Sesotho’s Pan-South African Ditema Tsa Dinoko, Korean Hangul by King Sejong The Great, as well as in those languages that I knew/was more acquainted with (Armenian, Georgian, Russian, German, French, English, Latin). I also computationally analysed sample texts in Xhosa to calculate occurrences of certain phonemes and diphthongs to inform my design.

Type

Example presented in Xhosa Mono Sans.

Alphabetic and abugida

In Xhosa language there is agreement within the sentence, and therefore an alphabetic written system is the most suitable to express the morphemes added to the words.

Clicks have been introduced to the Xhosa language due to the practice of hlonipha (avoidance speech), where carriers introduced new phonemes to change the important names that could not be otherwise pronounced. They are often used with a preceding change in sound (as well as a few other consonants), for which an “abugida” writing system will be introduced (where the glyph of click changes based on which phoneme precedes it in the word).

Here is an example of merging alphabetic and abugida systems in Xhosa. “c”, “h”, “n” are separate valid letters and phonemes. However, when near each other in a specific order, they are pronounced differently and therefore a new merged character is created for each of those.

Geometry

Xhosa village. Picture by Dr. Fundile Nyati.

Round, sans serif (no little perpendicular lines in the end of glyphs which is used by languages that engraved in stone, like Latin), colorful, can be changing boldness (but mainly mono)

Geometry of written language often depends on the medium that is available to write on/with. Usage of clay in construction suggests cuneiform as an available medium for writing which informs plenty of tall thin lines.

The Xhosa people mastered spear-making which is a ritualistic hereditary relict in each family. This suggests that they can easily possess a variety of tools for writing with fine precision along with using brush-like tools from cattle hair. Experienced agriculturalists, the Xhosa people possessed cattle which would allow them to use parchment which is a great medium to write smooth and round (also informed by round architecture) shapes with varying boldness. However, following the patterns of Xhosa dresses, where widths of color strokes are not varying, monoline can be suggested as a reasonable baseline.

It is also reasonable to suggest that the Xhosa people would use the colors that they use in dying their clothing for writing and calligraphy purposes. Typical palette of Xhosas can be viewed in this casual photo on the left.

Xhosa fabrics and designs by one of the most accomplished modern South African designers, Laduma Ngxokolo.

Orthography

Abrade or no separation of morphemes, space between “phrases”, left to right or boustrophedon

By its morphology, Xhosa is an agglutinative language, with an array of morphemes (prefixes and suffixes) being attached to root words according to 15 genders (morphological classes, accounted for numbers) of nouns. The verb is modified as well to mark subject, object, tense, aspect and mood. The agreement within various parts of sentence follows both class and number. This suggests none or abrade separation of morphemes and roots within Xhosa “phrases” (what in English would be called a “word”) that compose the sentence. The word order of subject-verb-object-(adjective) suggests usage of additional word (“phrase”) separator, such could be used as a blank space to save ink.

Alphabetic script allows linear writing, and the horizontal direction is the most suitable because the head’s left-right movement is easier for the human body than up-down, based on the constraints of vertebrae in the neck. In Xhosa culture, right is associated with good and prosperous and therefore left-to-right writing system is optimal to Xhosa mentality.

Later, another orientation can be explored — boustrophedon, which is right-to-left and then left-to-right alternating writing that was used in some ancient cultures. It saves energy to bring the head back to beginning of the next line. Boustrophedon also requires to flip the glyphs when writing from right to left since it makes it easier for the reader to know how to read and it is easier for the writer not to worry about saving space for longer “phrases”.

Numbers

Number glyphs with additive geometry from 0 to 9

Numbers in Ibhaliwe.

In Xhosa, it is decimal numerical system and larger numbers are constructed with addition, which informs an additive numeric system (where you can visually “extract” and “add” characters to perform arithmetic). Some adjectives are formed from repetition of nouns and for that reason a special “number-abugida” may be used to inform the reader. This could be done most efficiently if number glyphs are also created.

Capitalisation

No upper/lower cases

Nouns, and especially their roots, play a special role in Xhosa language, and even in some Latin alphabets the noun roots are written with capitalized letter. Within Xhosa community relationships are mediated often with recognition of each others’ clan names, which are more important than surnames and form social bonds. However, it is possible to use other visual cues to “capitalize” nouns and clan names, such as order and abrade. There is also a convention that the accent is usually placed on the penultimate vowel and once learned, there is no need to capitalize the accented vowel. For such reasons, capitalisation is not required.

Punctuation

Punctuation in Ibhaliwe.

“?” and “!” (variable strength) before the word, “didot” and “tridot”

In Xhosa language there is allowance to put question marks and exclamation points in the sentence on specific different words, and thus a special punctuation that is placed before the specific word (rather than at the end of the sentence) will be introduced. In addition, design of punctuation should allow variable strength of emotion (this is done by varying the number of dashes on the “?” sign and adding more “!” signs). Additionally, a comma will be indicated as “didot” and end of sentence punctuation will be introduced as “tridot”, according to symmetry relationships within Xhosas’ concentric architecture. Dots have round empty space in them (as well as many glyphs), following the conception of Xhosa communal households and settlements where the center of a village is populated by non-human objects/animals.

Forms of Nature

‘nc’ letter

Elephant-silhouettes, star-like and floral clustering of glyphs

Xhosa culture is tied with nature surrounding it. As such, calendar periods’ names are devoted to certain stars, constellations, trees or flowers. Moreover, clans have their animalistic and non-animalistic totems. For example, the clan name of interviewees has the sun and a sheep as their totems. Holistically, the elephant serves the most symbolic meaning, well aligning with peaceful (in comparison to Zulus) but persevierent people (during the 19th century, the Xhosa people in the Eastern Cape fought seven frontier wars against land dispossession by the British settlers, such that they were never conquered militarily like the British did with the Zulus). Elephants are also aligning well because Xhosas honor the members that passed away through an ancestral spiritual system (juxtaposed with elephants being one of the only animals burying their kin). For that reason, many of the free-floating ends of the glyphs are designed to remind the viewer of elephant-silhouettes and the combinations of glyphs that make up the new glyphs are formed in star-like and floral patterns (which are also reflected in floral-inspired designs of garments in the Xhosa culture).

Vowels

Satellite vowels.

‘oo’ letter as an ‘o’ with a satellite ‘o’

Xhosa has ‘a’, ‘e’, ‘o’, ‘u’, ‘i’ vowels, some of which are sometimes pronounced long. For each of these vowels a visual characteristic of tongue, lips and direction of the sound wave front was utilized to inform the form of glyph (for, example, a rising = tall ‘i’, a sagittally symmetric and wide lip = horizontal ‘e’). To avoid repetition, the long vowels have repeated satellite vowels in them.

Consonants

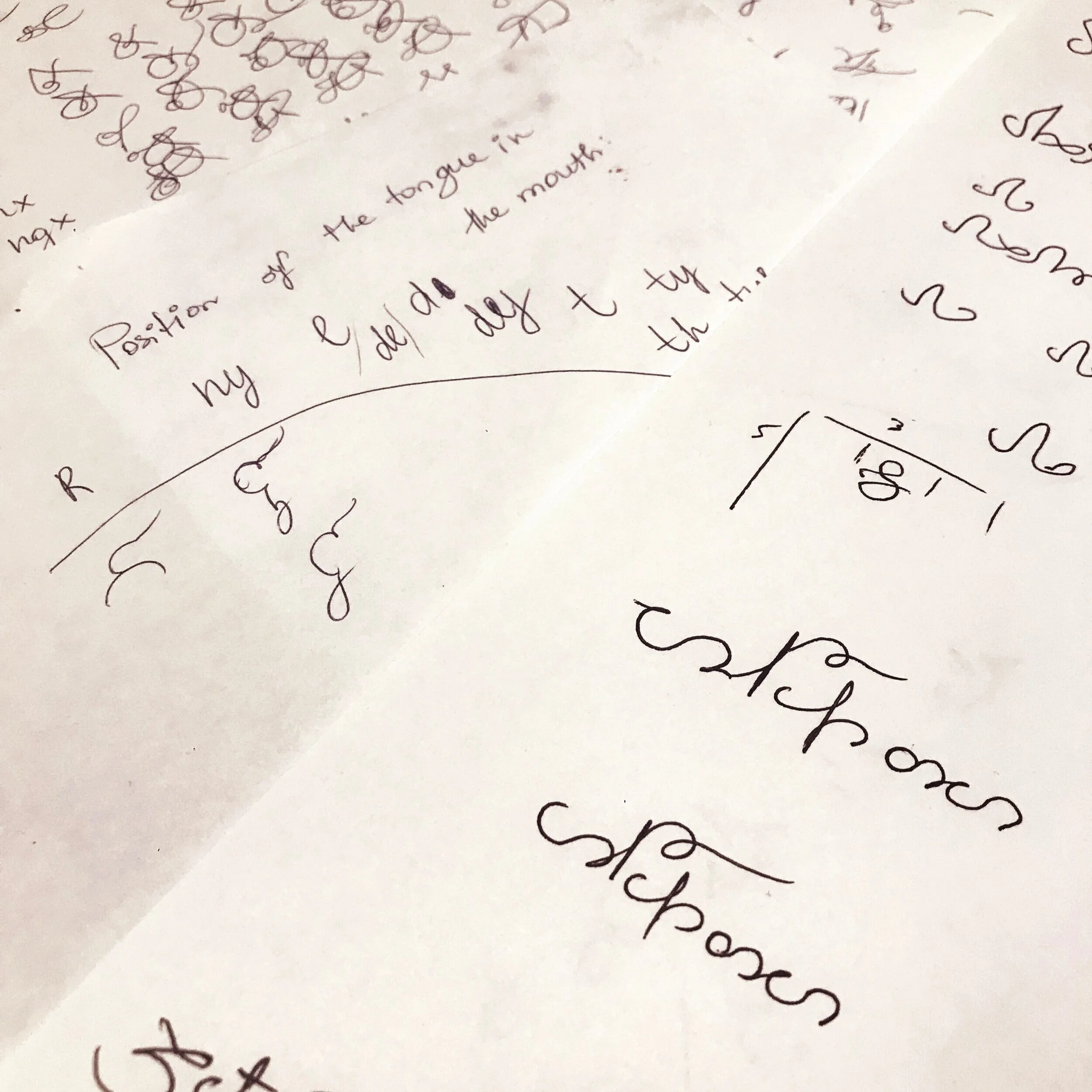

Glyph modification based on anatomy of sound-making

first Adobe Illustrator drafts of clicks

Consonants were grouped and lined up by similar characteristics, as in analysis with vowels (for example, follow the kernel of sound-producing unit from the front to back of the mouth: ‘b’, ‘bh’, ‘p’, ‘ph’, ‘t’, ‘th’, ‘ty’, ‘tyh’, ‘d’, ‘dy’, ‘dl’, ‘l’). Taking right as front (both associated with good) the kernel of character changes its position, modifying the glyph. See below for final results.

As mentioned before, abugida is used for click ligasions with the ‘h’, ‘n’, ‘g’, and ‘ng’ to form from the ejective click — aspirated, nasal, slack-voice and slack-voice nasal clicks, respectively.

Upon suggestion of one of the interviewees, some phonemes are so rarely used that their incorporation within the alphabet will be overcomplifying at this stage of the project.

Additional rationales. A: scooping movement with tongue and wave of elephant as a first letter. E: symmetric, horizontally opened lips, EE: repetition. I: clean like A, but higher frequency and tall, II: repetition. O: round lips, dot in the middle signifying of importance of empty space, OO: repetition. U: is contained by many words in Xhosa, including most frequently used ones, similar to ‘o’ lips, but descending voice. B: node in the right, P: lighter version of B, T: touch on the ceiling of mouth, D: same as B but on the inverse side of mouth, thus, reversed, L: inward breath and touching ceiling, N: opposite of L.H: descending breath and therefore goes down, adds to everything that has an H in diphthong or triphthong, such as BH, PH, TH, TYH, HL, CH, XH, QH, SH, ZH (not RH, which is rather a vibration in the back of the mouth like phoneme ‘kh’ and therefore left-sided knot on the upper side. Y: makes every diphthong softer and is directed downward, makes a knot such as TY, TYH, DY, NY. C: click that takes air in-between the teeth, explosive, and thus the x-like glyph. X: click taking air from the side of mouth horizontally and with all closed mouth, thus lateral movement and horizontal line within a circle. Q: click with knot in the beginning and then drop with a tongue. G: shallow knot in the top back of mouth, breath outwards, K: reverse of that. S: stochastic oscillations with tongue in the top upper inner teeth-side. SH: same, but with quick drop and ‘h’. Z: more defined knot. V: dropping and undefined knot. F: opposite movement.